Reading part 1 about the core is recommended as some of the preliminary remarks there are also relevant to this discussion. It must be stressed that much of the information about the earth’s interior is inferred as direct observation is not possible.

The outer region of our planet, the Bulk Silicate Earth (BSE), is thought to to be composed of layers. The stratification or differentiation of this region of the earth into layers is a major feature and forms the basis of descriptions of its morphology, that is, its form and structure.

The reasons for this layered structure are much discussed and investigated. Note also that layered structures appear over a wide range of scales. As the name Bulk Silicate Earth suggests, silicate is the main component of the layers and oxygen is the main component of the silicate.

These layers are preceded by the hydrosphere/atmosphere and followed by the inner/outer core. The layers are distinguished by variations in one or more of the following categories.

1. Elemental composition. Elements are classified according to the number of protons in their atomic structures, the protons reside in the nucleus of the atom along with neutrons. There are about one hundred known elements and the earth contains all of the naturally occurring ones in varying proportions. Examples are hydrogen (1 proton), oxygen (8 protons), iron (26 protons), carbon (6 protons), mercury (80 protons) and so on. Elements may have components called isotopes. These isotopes have differing numbers of neutrons combined with the fixed number of protons of the element.

2. Mineral content. The elements are combined into various chemical compounds called minerals which, nearer the surface at least, are generally crystalline in nature (that’s where the mineral components have an ordered periodic structure), but occasionally they are amorphous (i.e, no crystal structure, like for example, glass, or indistinct, like talc). The size of the crystals can vary from very large to microscopic. There are about 5000 different minerals. They can occur as separate deposits or combined with other minerals as rocks. And it just so happens that the majority of the mineral volume of the BSE is composed of various types of silicates (silicon oxides which are a combination of the metal Silicon and the gas Oxygen) with other metals, for example, magnesium silicate or aluminium silicate.

3. Rock types. Rocks consist of different combinations of minerals. Examples of rock basalt or sandstone. The minerals that constitute the rocks are generally crystalline. The rocks are divided into three separate groups, igneous (intrusive or extrusive), metamorphic and sedimentary. These categories are based on what are thought to be varying formation conditions and origins. However, like the layers of the earth themselves, the boundaries between these rock groups are sometimes blurred. There are a few hundred different rock types spread over the three principal classes.

The most abundant rock type are the Igneous rocks which are presumed to have solidified from a magma (a body of molten rock). The magma can take the form of subterranean lakes, layers, plutons, plumes, pipes, sills and and dykes. Magma appears on the surface as sheets of basalt (less often, rhyolite), or as exposed plutons/dykes or volcanic ejecta.

The magma interacts with the rocks with which it comes into contact, to the extent that some of the host rock becomes incorporated into the magma and transported elsewhere. The interaction can also modify the mineral structure and content of the host rock.

The magma composition can vary depending on the source of the magma itself. Most is considered to have a mantle zone origin although often influenced by subducted crust and its accompanying sediment and water (as liquid or in sepentinized crust – the water enables the components to liquefy at a lower temperature than would otherwise be the case). Other melts such as granite magmas may have their origin in reworked sediments. The magma is thought to be enriched in lower melting point elements as it solidifies, leaving heavy metal rich silica structures either as disseminated or veined deposits in the solidified magma or the surrounding host rock. Diffusion and fracking are the operative processes.

The other rock types present in the crust are:

Sedimentary, (includes sandstones, mudstones, coal, claybeds, ironstone, conglomerates, evaporites, hydrothermal or biotic limestone, some metal sulphide deposits). They usually have a layered structure and often display varves which suggest an advancing front of deposition which is typical of deltaic sediments. Sedimentary deposits can be regionally extensive and thousands of meters thick. The majority of sedimentary rocks are considered to have a detrital origin, i.e. transported by water (including glacial activity), wind or gravitational collapse to the site of deposition.

Others are thought to have been deposited by evaporation or by hydrothemal activity. The carbonates (e.g. limestone) are considered to have a biological origin, however recently a hydrothermal carbonate has been identified where the source of the carbon is ocean floor methane seep. These Methane Derived Authigenic Carbonates (MDAC’s) occur as ocean floor structures or as subsurface features that can be identified in seismic surveys.

Some clays have also been shown to have an authigenic origin. Clays usually underlie coal seams. In addition some sandstones are now identified as injectites originating at a lower level and some buried evaporite sediments such as salt occur as buoyant plumes in the surrounding sediment which sometimes break the surface forming a salt glacier. Most sediments form in oxygen rich zones but some such as coal appear to have formed in an environment depleted of oxygen.

Metamorphic. These are originally igneous or sedimentary rocks that have been altered as a result of exposure to high temperatures and pressures (high energy) either as a result of burial by subduction, overturning or sediment overburden accumulation. Metamorphism can also occur as a result of coming into contact with intrusions of some kind either as dykes or plutons (a large subterranean magma blob). Other tectonic action uplifts them to near the surface where they outcrop. They are the source of much of the worlds supply of ferrous (banded iron formations) and non-ferrous metals. The source rocks, when they return from their journey to the underworld where they encounter high pressure and high temperature conditions, are highly altered and deformed and sometimes enriched with heavy metal sulphides etc.

Metamorphics are generally classified according to the amount of pressure and temperature to which they are thought to have been subjected. An example of a common metamorphic rock is slate.

4. Physical conditions including,

a. Temperature,

b. Pressure,

c. Structure e.g. boundary morphology, faulting etc.,

d. Electrical properties such as conductivity, magnetic properties etc.

e. Thermodynamic considerations such as

i. Energy sources,

ii. How the energy is transmitted, the nature of these flows/transmissions including electromagnetic and acoustic (seismic) activity, radiation, mantle flows/plumes, convective or otherwise, and conduction.

iii. Its effects, e.g. tectonic activity/earthquakes, deep earthquakes (non-tectonic), vulcanism, radioactivity, optical properties, fault propagation patterns.

iv. The phases or states of the components: solid, liquid/gel, gas, plasma or maybe even some high temperature/pressure analogue of the fifth state of matter, Bose-Einstein condensates.

Aspects of these categories are referred to where appropriate.

The Layers and Boundaries.

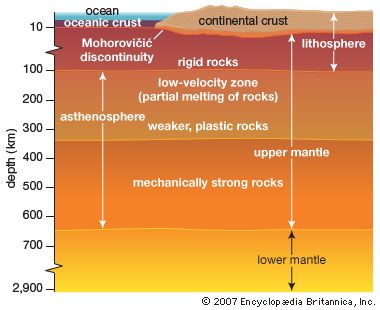

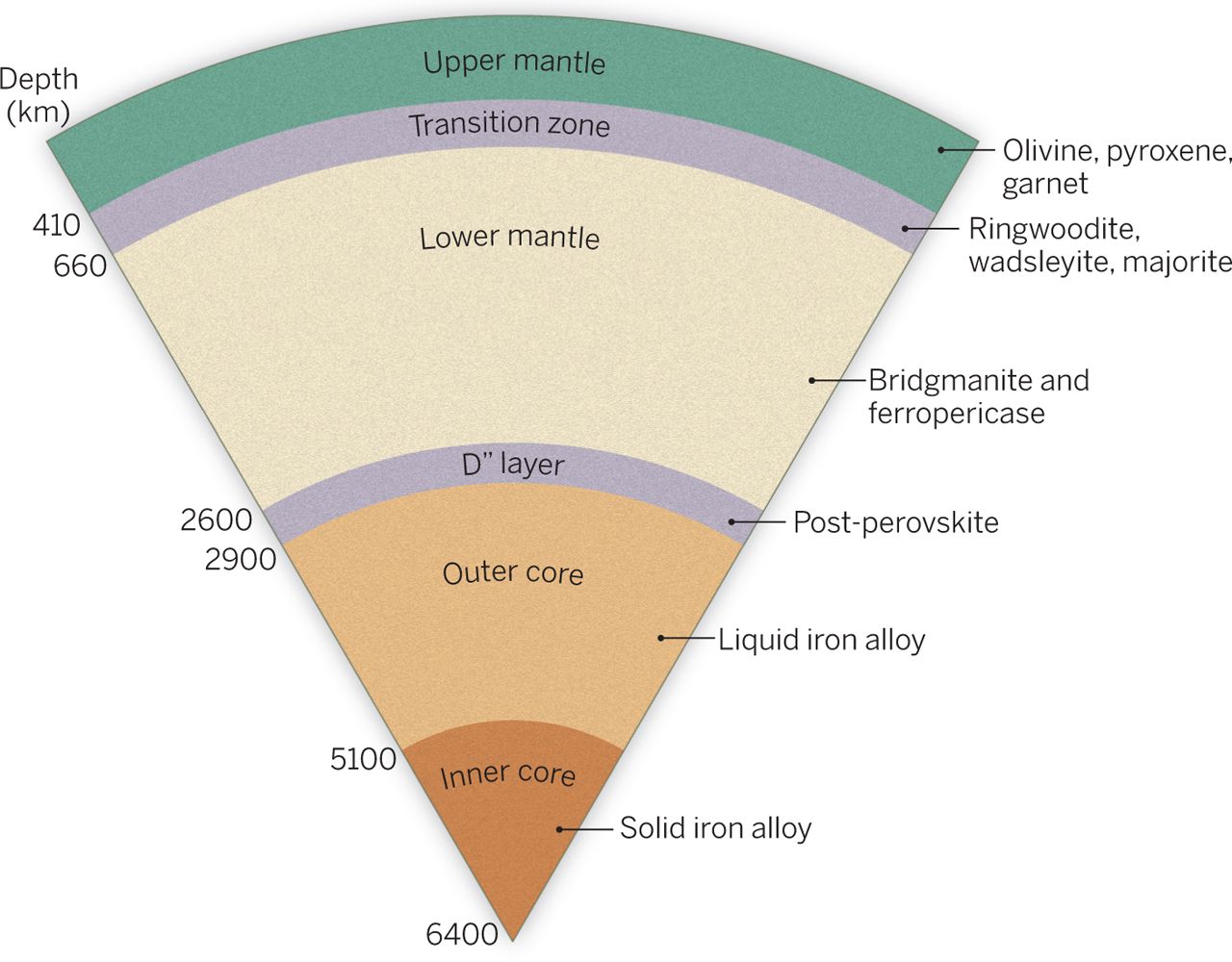

The following is a list of the layers and discontinuities of the BSE from the surface down. Some of the layers are based on chemical composition while a few distinguish different mechanical properties (lithosprere, asthenosphere and mesosphere). They generally follow one another but sometimes they overlap other recognised boundaries. Estimates of the size of the layers vary but the figures provided give a rough idea of their extent and order in which they occur. Layers and boundaries can be distinguished by variations in seismic wave transmission paths and velocities whereas the composition layers are inferred from a study of what is thought to be mantle type rock exposed on the surface, stony meteorite composition, high temperature/pressure studies of various elements, compounds and minerals, and gravitational surveys.

Crust, there are two types, oceanic crust 5-10 km thick which covers about two thirds of the earth’s surface and is generally less than 150 million years old. The remaining one third is continental crust (including continental shelf areas). This part of the crust is up to 70 km thick and up to 4.5 billion years old. As well as the age difference, the two types of crust differ markedly in composition with the ocean crust being basaltic while the continental crust is granitic.

Conrad discontinuity, observed in some continental regions at a depth of 15 to 20 km, however it is absent in other continental and all oceanic regions. Unlike the more well known Mohorovičić discontinuity (Moho), it is somewhat indistinct, and it may be related to the 19th century notion of dividing the crust into an upper felsic sial (silica-aluminium) region containing rocks such as granite, and the lower, magnesium-rich mafic sima, (silica-magnesium) consisting of andesitic type rocks. See below for more on the mafic/felsic classification.

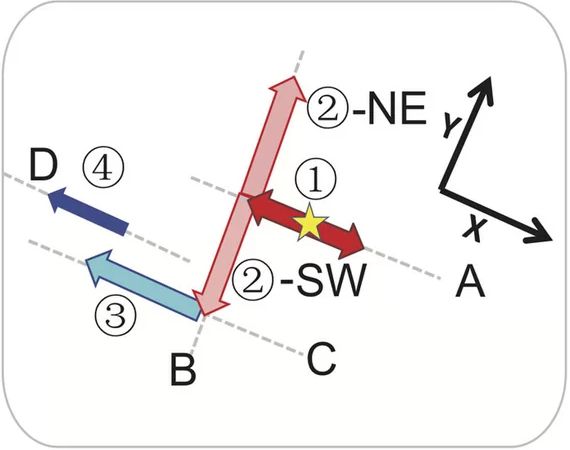

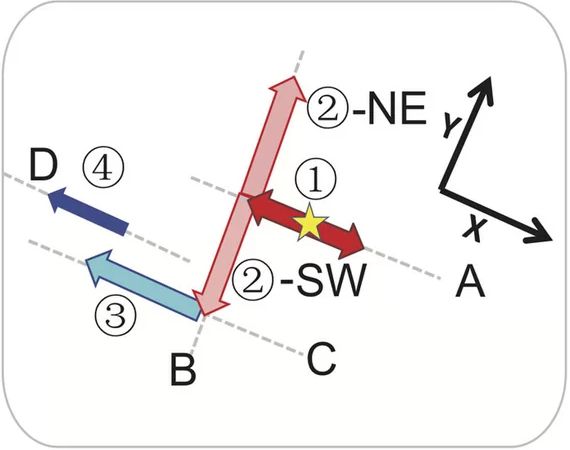

Brittle to ductile transition zone. This is the strongest part of the Earth’s crust. In the felsic rocks of the continental crust it is located at an approximate depth of 13–18 km (roughly equivalent to temperatures in the range 250-400°C). At this depth rock becomes less likely to fracture and more likely to deform by creep. Many earthquakes occur in this region. They are generally the result of propagating horizontal or vertical movement, or both, along a fault, which can be exposed at the surface or hidden, in a process that can be likened to unzipping. The disturbance generally propagates in both directions along the fault, although in some large earth quakes at least, the fault propagation is more erratic and discontinuous, often following an orthogonal or zigzag path and sometimes having parallel paths. Faults unzip at speeds of about 2.5 Km/s, (in contrast, in some deeper earthquakes the rupture rate can be as much as 8 Km/s).

Below is a representation of how the unzipping propagated in the 2012 Sumatra earthquake with the rupture starting at the star labelled 1.

Credit: Lingsen Meng et al., Caltech.

Mohorovičić discontinuity (Moho), it is located about 5-10 km below the ocean floor, and 20-90 km (average 35 km) beneath continental crusts. It is characterized by an increase in primary seismic wave (P-wave) velocity from about 7 km/sec to about 8 km/sec. It is suggested that it marks a change in rock type from basalt to peridotite, however it is a very regular interface and other observations suggest that such a variation in rock type would have a more uneven boundary. The Moho is characterized by a transition zone of up to 500 m thick. The P-wave velocity range for basalt is 6.7–7.2 km/s and for peridotite or dunite it is 7.6–8.6 km/s and as they do not overlap this makes for a sharp boundary.

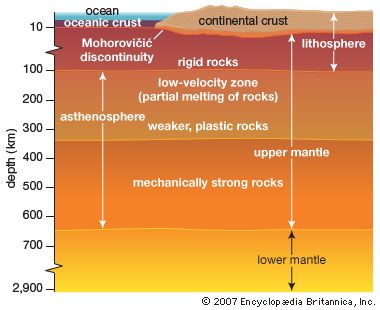

Lithosphere, defined to be the rigid outer layer, it includes both the crust and the upper portion of the mantle, and is about 150 km thick. This identity, like the asthenosphere mentioned below, is a mechanical classification. The lithosphere is the province of tectonic plate activity where the layer of ocean basin rocks, down to the base of the lithosphere, are thought to be continually recycled via a process which is a combination of subducting old cold ocean crust and its replacement with new material introduced via mid ocean ridge spreading. The energy source for this process is not well understood.

Lehmann discontinuity, like the Conrad discontinuity, a somewhat ephemeral feature that manifests as an increase in P and S wave velocities at 220±30 km. It is present below continental crust, but is much rarer beneath oceanic crust, and is not readily apparent in globally averaged studies.

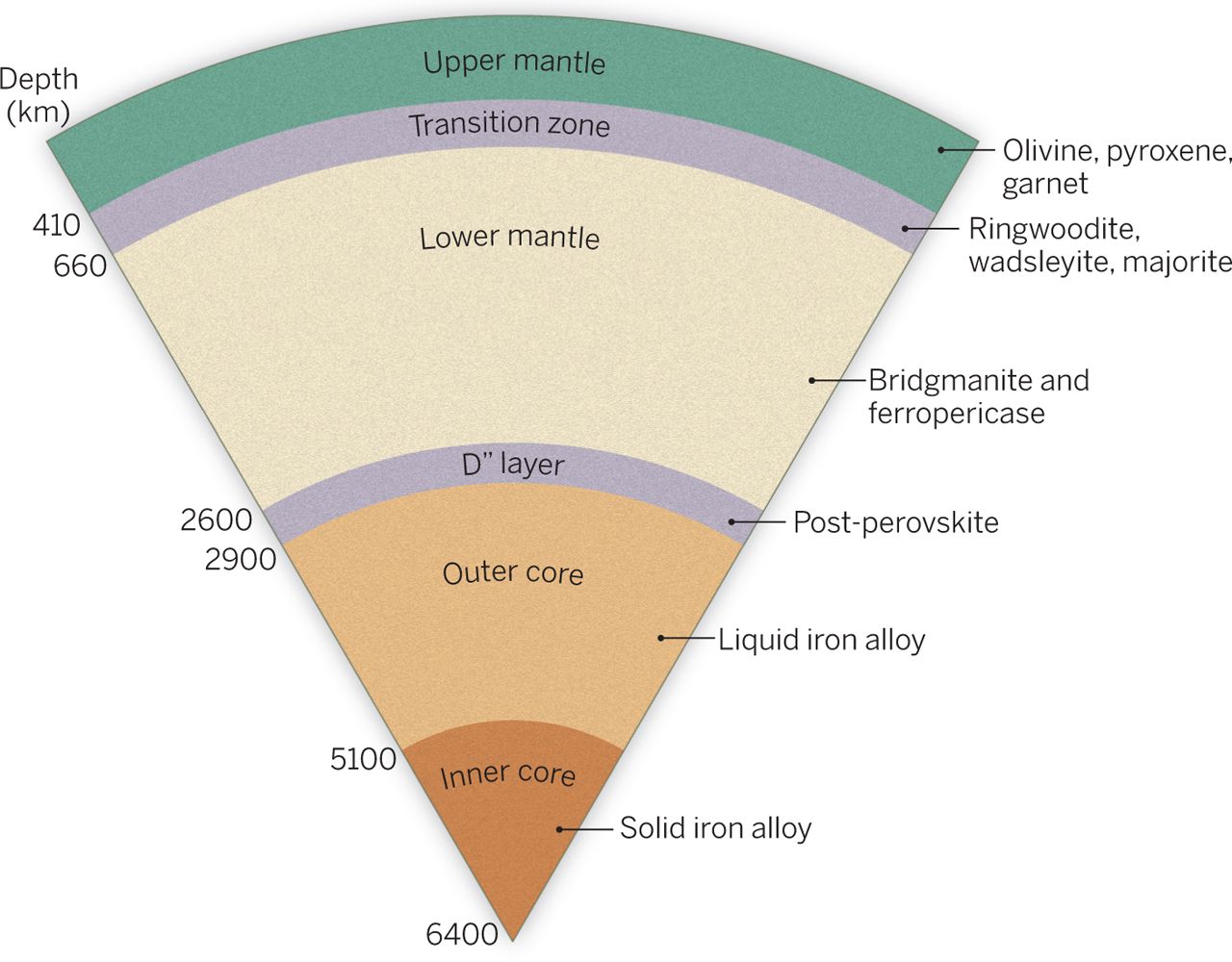

Upper mantle, the first 400 km of the mantle. It is composed of the magnesium-iron silicate variants, olivine, pyroxenes and garnet. It plays host to magma formations and is believed to be penetrated by more dense sinking cold oceanic crust/top of the upper mantle combination (lithosphere). The regions where this occurs are located at plate boundaries and are called Wadati-Benioff or subduction zones. This process introduces water to the inner region and so enables the creation of shallow magma bodies that can make their way to the surface and manifest as volcanic activity. Volcanic activity that is not related to subduction zones, for example in the Hawaiian islands, produces only the mafic basalt and has a much smaller amount of volatiles. These intra-plate volcanos are thought by some to be the result of plumes of positively buoyant mantle material ascending from deeper in the mantle. Interestingly, the base region of the upper mantle, where the olivine minerals of the upper mantle transition to the spinel minerals of the middle mantle, is generally aseismic, i.e. earthquake activity is uncommon at this depth.

Middle mantle or Transition layer, about 250 km thick, it extends down to about 650 km. It is thought to be composed of yet more magnesium-iron silicate variants, spinel and majorite. The lower boundary of this zone roughly coincides with the limit of deep earthquake activity and the depth of this lower boundary is shown, via seismic data, to be uneven, rising here and falling there by up to about 50 kilometres. The reason or reasons for the (somewhat unexpected, …at these depths one might expect the boundary to have eqilibrated over time) variation are not well understood but may relate to varying conditions in the lower mantle.

Seismic data also suggests that the general topography of the lower boundary can have the scale and variability of a medium size mountain range, i.e. a vertical range of around 2 or 3 kilometres. The presence of this discontinuity may also mark the limit of the convection currents thought to transfer heat energy outwards from the core region, …with perhaps another convection system (this proposed secondary convection system is, along with gravitational collapse, thought to drive the tectonic activity of the crustal plates) operating above the boundary region in the upper mantle. However the apparent similarity of the of the chemical composition of both the upper and lower mantle rocks and the transition layer itself makes the presence of a double layered convection system model problematic in that double convection layers usually require chemically distinct compounds, such as oil and water.

The transition zone hosts deep earthquakes, which account for a small fraction, less than 4%, of total earthquake energy. They mainly occur near plate boundaries, in particular, on the western flank of the Tonga trench and more generally, around the Pacific except for the North American portion which is quiet at this deep level. The origin of these short duration, high energy events (explosions) is something of a puzzle in that brittle fracture of the rocks may not be possible at these depths due to their high ductility in a region where the temperature is thought to be about 1600°C. A rapid change in fluid pressure might be a more appropriate description of the source of these deep disturbances. The rapid de-watering of the serpentine minerals in down going slabs has been suggested as a possible mechanism for pressure variation (this de-watering is also thought to enable the formation of magmas in the mantle rocks above the descending slab). The rugged nature of the boundary topology suggests perhaps that vertical displacement could play a part in the generation of these deep earthquakes. Variations in the thickness of the zone or rapid overturning may also play a part in their generation. The limited observations give no indication of how much the boundary might change over time.

Asthenosphere, this is the other mechanical layer classification, it extends from the lower boundary of the lithosphere down to the lower boundary of the middle mantle which, as stated above, is at a depth of about 650 km. It thought to be a region composed of very viscous, mechanically weak, ductile mafic material. And its lower boundary roughly coincides with the depth limit of deep earthquakes.

Lower mantle, extends from about about 670 km to 2,700 km. Thought to be composed of yet another magnesium-iron silicate variant, silicate perovskite (Mg,Fe)SiO3 (also known as bridgmanite) combined with calcium silicate (CaSiO3) and arranged in a perovskite structure. Together with ferropericlase, which is the oxide of the ubiquitous magnesium and iron ((Mg,Fe)O), these minerals are thought to be the stable mineral phases of this region.

Spin transition zone. … Changes in the spin state of electrons in iron in mantle minerals have been studied experimentally in ferropericlase. … Results indicate that the change from a high to low spin state in iron occurs with increasing depth over a range from 1000 km to 2200 km.The change in spin state is expected to be associated with a higher than expected increase in density with depth. …

‘D’ layer, the last 150-200 km of mantle, between 2700 and 2900 km with a base temp of 2200 C, thought to be composed of a another in the perovskite sequence, post-perovskite and ferropericlase which is the stable phase at the temperatures and pressures encountered at those depths.

Gutenberg discontinuity delineates the core mantle boundary

Note: The seismically reflective inner core boundary, known as the Bullen discontinuity, is also sometimes referred to as the Lehmann discontinuity as it was first observed by Lehmann. Confusing, no? 🙂

This diagram, courtesy of Britannica, shows how the mechanical classifications overlap the compositional layers.

Reiterating a couple of points mentioned above, the bulk silicate earth includes both the mantle and the crust. It extends from the surface to the core/mantle boundary. And the seismically identified boundary region between the mantle and the core is found at about 2600 km below the surface and is known as the ‘D’ layer.

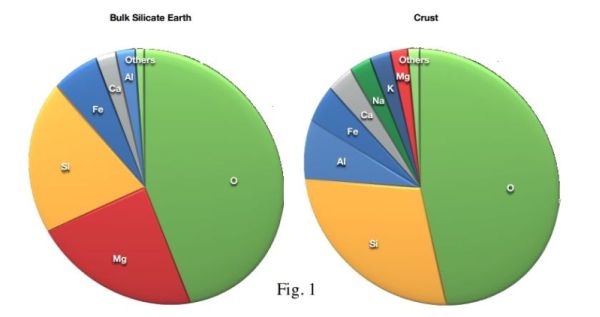

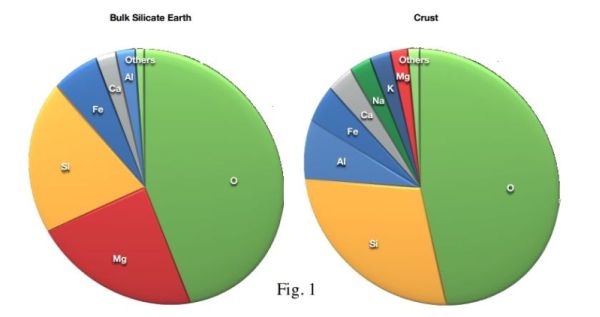

In contrast to the mainly iron core, the BSE consists mostly of oxygen, silicon and magnesium, combined with lesser amounts of iron, aluminium and calcium along with even smaller amounts of sodium and potassium, and more controversially, with perhaps significant amounts of hydrogen, carbon or sulfur (see below for a more precise accounting of proportions).

Unlike the core, where the elements exist in their reduced state (i.e. as metals or metal hydrides), the metallic BSE elements are generally combined with lighter elements (oxygen, sulfur, hydrogen) in what is termed an oxidized state where the metal atoms are depleted of one or more electrons. These depleted electrons are shared or appropriated to some degree by the other atoms in the molecule (a combination of atoms) and serve as part of the binding energy that holds the molecules together. These combinations of elements are known as chemical compounds or minerals. For example most of the mantle consists of some form of magnesium or ferro-magnesium silicate (together with calcium silicate) which, as the name suggests, is a combination of the three principal mantle elements, silicon, oxygen and magnesium.

Combinations of these compounds/minerals are the main components of rocks (they can also contain smaller amounts of metals, liquids and gases). Although the BSE contains a significant amount of metallic elements, they are generally combined with silicon and oxygen to form rock minerals and rock minerals are the components of rocks. Hence we deduce that, in contrast to the metallic core, the BSE is rocky.

One of the pieces of data that assist in our understanding of the earth’s interior is the estimate of the earth’s bulk density. The bulk density of the earth is calculated to be about 5.5 gm/cm3 (in comparison, water is 1gm/cm3) but the density of the crust and exposed mantle rock is usually less than 3 gm/cm3, so a dense core is required to reach the overall density of 5.5 gm/cm3 , hence the iron core model. In addition, mantle seismic data reveals numerous discontinuities where the wave velocity steps up or down suggesting a change in density or composition at those levels.

The composition of stony meteorites is also taken into account when modelling mantle composition. At normal temperature and pressure, rocks display a very wide range of densities. They can vary from about 0.3 gm/cm3 for calcium silicate to 3.4 gm/cm3 for gabbro. The first of these, calcium silicate (along with magnesium-iron silicate) features prominently in the lower mantle while gabbro is thought to constitute up to 90% of the ocean crust.

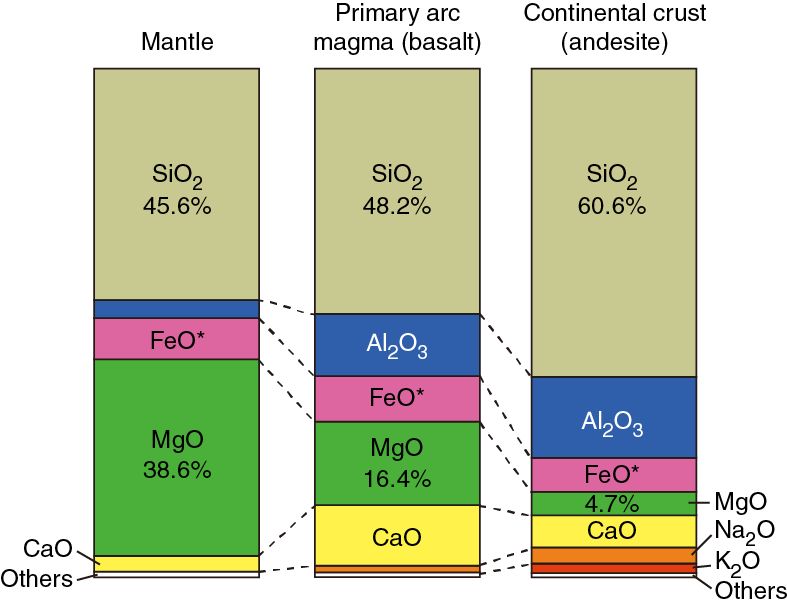

The most significant elemental difference between the rocks/minerals of the crust and those of the mantle is their magnesium content. The chart below shows the composition of the mass of the bulk silicate earth (BSE) and the crust. The crust is about 1% of the BSE, so the BSE estimate can be taken as an analogue for mantle composition. The most abundant elements are oxygen and silicon.

Note how oxygen is main component of both the crust and the mantle, it accounts for nearly half of the whole BSE by mass, and a surprising 94% of it by volume. Note also the large variation in magnesium (the red wedge is magnesium) between the mantle and the crust. There is a lot in the mantle, 22.8% and much less in the crust, about 2%. Note also that magnesium and silicon are very close in the periodic table of elements (separated only by aluminium) with atomic numbers of 12 and 14 respectively. The role of magnesium in mantle rocks is reflected in the names given to that class of rocks, the terms are mafic and ultramafic (see discussion below).

As well as magnesium, the other minor elements of the crust are, aluminum – 8.1%, iron – 5.0%, calcium – 3.6%, sodium – 2.8% and potassiun – 2.6%

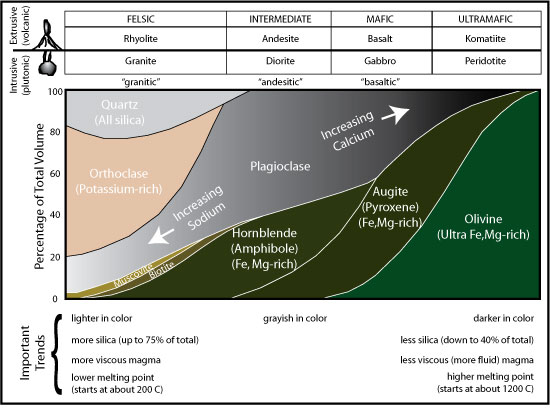

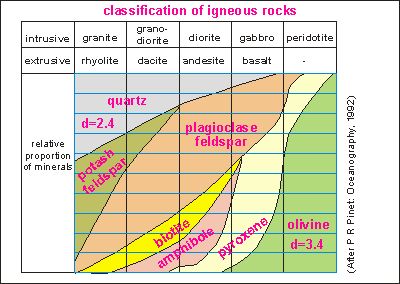

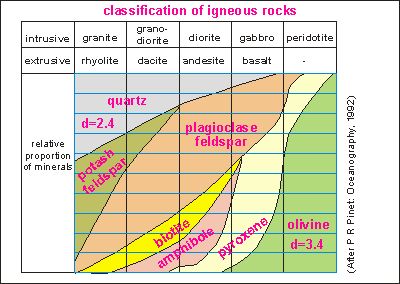

One can roughly divide igneous rocks (rocks that have a magmatic origin) into two types, 1. Felsic which combines the words feldspar and silica or

2. Mafic which combines the words magnesium and ferric). Mafics also contain silicate but in smaller proportion to the felsic rocks.

A similar classification divides rocks according to their silica content. Those with high silicate content are labelled acid while low silicate rocks are labelled basic. The in-between ones are referred to as intermediate rocks.

The igneous continental crust rocks are generally felsic while the ocean crust and the mantle rocks are generally mafic. But mafic rocks are also present in the continental crust as intrusions or ocean crust fragments or volcanics or even as exposed metamorphics.

The magnesium and iron rich mafic minerals that are encountered on or near the surface are usually dark coloured, with densities often greater than 3 gm/cc. Some common types include olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite.

Another mafic mineral, serpentine, is found as an alteration product (it is a hydrated form of the original mineral) of other mafic minerals like pyroxene and olivine. As such it occurs as a pseudomorph (meaning it retains the external shape of the original mineral) of the crystals it replaces while the actual crystal structure of serpentine itself is indistinct as it is composed of a fine admixture of about twenty different varieties.

Serpentine is one of an important group of minerals called phyllosilicates that also includes the metamorphics mica, chlorite, talc, as well as the clay minerals. Phyllosilicates can be either mafic or felsic, their distinguishing feature being a silicon oxide ring structure, a bit like carbon’s benzene rings. Clay is one of the major constituents of sedimentary rocks and much of it has an authigenic origin.

Serpentine also features of in a group of metamorphosed ultramafic (extra high magnesium), high melting point extrusives (lavas) and sub-volcanics called komatites. They are thought to originate deep within the mantle and somehow manage to become enriched with heavy metals as the buoyant magma ascends to the surface (how they maintain buoyancy as they become enriched with metal is something of a mystery). They are restricted to the older shield regions of the crust and are generally adjacent to granite pluton material and show typical lava characteristics such as pillow structure and evidence of surface cooling.

All komatite formations have experienced some degree of metamorphism so strictly speaking they are metakomatites. Serpentinization (hydration) and carbonation are defining features of all komatites. The alteration is a function of the carbon dioxide and water content of the fluids encountered, producing respectively carbonates or serpentine. Komatites are very rich in magnesium and depleted in silicon, and as such the liquid phase is very mobile having the consistency of water. They are often differentiated to the extent that the base of the flows sometimes contain channels that contain a layer of metal sulphides overlain by enriched lava. The altered lava generally consists of serpentine pseudomorphs of olivine or other magnesium rich silicate minerals and/or magnesium carbonate. In some places the mineralization levels can be exploited/mined for the production of the metals such as nickel and uranium.

Kimberlites (CO2-rich ultramafic potassic mantle-derived volcanic and subvolcanic rocks, often brecciated (fragmented) dominated by olivine/serpentine and carbonate minerals), and lamproites (ultrapotassic mantle-derived volcanic and subvolcanic rocks with high potassium and high magnesium content) are another manifestation of komatite rocks originating in the mantle. They occur as pipes and dykes and some of them contain diamonds.

While on the subject of serpentine there are a couple of other points worth noting. First, it has an odd crystal habit where the crystal structure has either a fibrous structure (somewhat polymer like) or a fine aggregate or admixture of closely related crystal structures. The fibrous structure consists of a series of curved plates of serpentine crystal matrix joined together in one-up one-down fashion so as to form a corrugated or crimped fibre. The plates are curved due to different crystal structures on either side of the plates. Serpentine itself is actually a combination of about 20 different varieties or polymorphs with the three most important being antigorite, chrysotile and lizardite. Antigorite is especially important as it is about 13% by mass water.

The metamorphics in general are inhospitable to plant life due to a lack of phosporus (P) and potassium (K) and no doubt the toxic metals, e.g. nickel (Ni) , chromium (Cr), cobalt (Co) they sometimes contain, also take their toll on plant life. It is also somewhat ironic that a polymorph (same chemical composition, magnesium silicate, but different crystal structure) of what is thought to be the most abundant mineral in the mantle, the metamorphic mineral asbestos, is now shunned in the west as a dangerous carcinogen. Man made magnesium silicate is amorphous (meaning it has no crystal structure) and is porous giving it a very high surface area to mass ratio, i.e it is very absorbent. It is considered to be biologically inert which is a good thing as it is ubiquitous as an anti-caking agent in salt.

Common mafic rocks include basalt, dolerite and gabbro. Mafic rocks often also contain calcium-rich varieties of plagioclase feldspar. Mafic lava has a low viscosity due to the lower silica content in mafic magma whereas felsic lava, with a higher silicate content has a higher viscosity. At the surface this difference manfests as extensive sheets of mafic rocks like basalt.

Another mafic mineral, silicate perovskite, is thought to be the main constituent of the lower mantle, possibly up to 93% by volume.

Felsic minerals are silicates of the lighter elements such as aluminium, sodium, and potassium. Common felsic minerals include quartz, muscovite commonly known as mica, potassium-rich orthoclase feldspar, and the sodium-rich plagioclase feldspars. In some cases, felsic volcanic rocks may contain phenocrysts (inclusions) of mafic minerals. They are usually light in color and have densities less than 3 gm/cm3, generally about 2.6 gm/cm3.

Although density is mostly related to the atomic mass of the atoms themselves, the density of a body is also affected by its electron structure. For instance, it is known that increased density is associated with the state of the spin structure of the electrons, in iron at least.

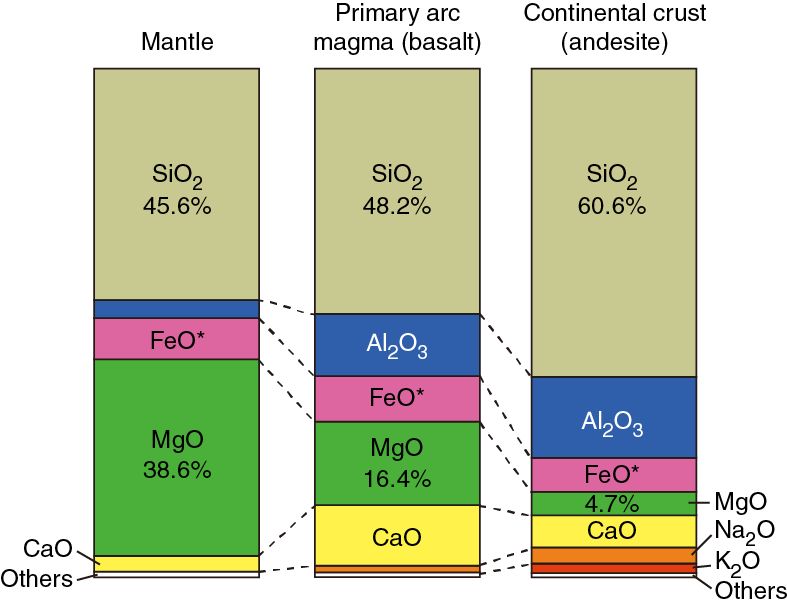

The most familiar felsic rock is granite while another felsic rock, andesite, is thought to form the majority of the base of the continental crust. Somewhat paradoxically, andesite is also the most common rock type erupted from volcanoes. Even intra-oceanic volcanic arcs, which are the product of converging ocean crust (basalt) erupt andesite. Exactly how the less dense, higher silicate, low magnesium andesite is derived from high density, lower silicate, high magnesium basalt is the subject of much discussion. In addition, inter-oceanic andesites often host veined or disseminated metals and metal sulphides, carbonates etc. In addition, andesite magmas or their precursors appear to be the source of the metals.

As mentioned above, the crust consists of two main types of rock, continental crust and ocean crust. they differ markedly in age and composition and thickness, chalk and cheese really. The majority of ocean crust is thought to be less than 150 million years old while we measure the ages of crustal rocks in the hundreds of millions to billions of years old. It is thought that the older ocean crust has been replaced by more recent magma upwellings. The older crust, by dint of its slightly higher density and lower temperature is thought to sink into the depths of the mantle with some being reduced to magma and eventually be recycled to the surface via vulcanism and other types of intrusion.

There is now general agreement that the surface (down to an uncertain depth but including both the crust and an upper portion of the mantle) rearranges itself over time. Crustal displacement or tectonics is thought to be powered by convective heat flows in the mantle with the necessary energy being transferred from the presumed energy source, the lower mantle. However as mentioned above neither the mechanism nor the energy budget for the process is well understood. And again as mentioned above, the crust is a only a very small portion of the overall bulk silicate earth. As one observer puts it,

“This narrow stratum as compared with the diameter of the Earth is but one half the thickness of one leaf of a thousand-page book.”

With the average crust thickness being measured in tens of kilometers and the mantle in thousands, a picture emerges of a thin skin covering a generally more pliable mantle, and compared to the interior this skin or crust is highly depleted in magnesium, …but enriched in silicon and with extra aluminium, sodium and potassium.

The rocks of the crust can be roughly divided into the the silicate rich, felsic continental crust which has a diverse array of rock types, and the more homogeneous mafic ocean crust, 90% of which is composed of the mafic rock gabbro. The age of the oldest regions of the continental crust is measured in billions of years while the ocean crust is generally less than 150 million years old.

The following chart shows how the elemental composition changes as one transitions from mantle rocks to ocean and continental mantle rock derivatives. Note that continental crust rock is enriched in silica and to a lesser extent aluminium but depleted in magnesium. The chart below shows how the silicate content increases and the magnesium content decreases as one progresses from the mantle to the crust. The proportions of oxides of metals generally reflects the proportions of the metallic elements.

The next diagram shows how rocks vary in mineral content and density. From left to right, the silicate content decreases while the density increases.

The evidence for the presence of water rich minerals in the upper mantle comes, somewhat ironically, from meteorite material which is rich in magnesium silicate. As already mentioned (but it bears repeating 🙂 ), the mantle is thought to be rich in magnesium whereas the crust and the core are depleted of magnesium, so the magnesium rich minerals in the meteorite are taken to be analogues of some of the mantle minerals. The water and other volatiles are thought to be introduced to the upper mantle via transport from the surface by subducted ocean crust. In fact all of the hydrogen and carbon in the mantle are thought to have their origin on the surface.

This idea, that subducted or infiltrated surface water is the sole source of inferred mantle water, is being challenged. It has recently been suggested that water may be present in large volumes, in the upper mantle at least, and computer modeling suggests that some of the water may be authigenic in that it is formed in situ from a reaction that reduces silicate (an oxide of the metal silicon) thereby releasing oxygen which then combines with free hydrogen or reacts with a metal hydride to produce water. There is not much discussion about a possible source of hydrogen in the mantle. Mantle water and mantle chemistry in general is currently a very active field of research.

The lower mantle is thought to be mainly composed of various analogues of magnesium silicate that can exist in the extreme temperatures and pressures of the region.

The following quote gives a description of how the various stables phases of magnesium silicate analogues progress from one phase to the next.

…At the high temperatures and pressures found at depth within the Earth the olivine structure is no longer stable. Below depths of about 410 km, olivine undergoes an exothermic phase transition to the sorosilicate, wadsleyite and, at about 520 km depth, wadsleyite transforms exothermically into ringwoodite, which has the spinel structure. At a depth of about 660 km, ringwoodite decomposes into silicate perovskite ((Mg,Fe)SiO3) and ferropericlase ((Mg,Fe)O) in an endothermic reaction. These phase transitions lead to a discontinuous increase in the density of the Earth’s mantle that can be observed by seismic methods. …

Here are the chemical formula of some typical mafic mantle minerals.

Olivine, an upper mantle mineral, – a solid solution of Mg2SiO4 Fe2SiO4. in variable ratios.

Serpentine, a derivative of an upper mantle mineral, – Mg3Si2O5(OH)4

Perovskite, a lower mantle mineral which, when combined calcium silicate may constitute 93% of this region – (Mg,Fe)SiO3.

Due to its unusual properties perovskite is presently a very hot research topic. Another quote from Wikipedia explains the reasons for the attention:

… Perovskite materials exhibit many interesting and intriguing properties from both the theoretical and the application point of view. Colossal magnetoresistance, ferroelectricity, superconductivity, charge ordering, spin dependent transport, high thermopower and the interplay of structural, magnetic and transport properties are commonly observed features in this family. These compounds are used as sensors and catalyst electrodes in certain types of fuel cells and are candidates for memory devices and spintronics applications.

Many superconducting ceramic materials (the high temperature superconductors) have perovskite-like structures, often with 3 or more metals including copper, and some oxygen positions left vacant. One prime example is yttrium barium copper oxide which can be insulating or superconducting depending on the oxygen content. …

It is apparent that doped perovskite-like compounds have all the makings of the being next big thing in semi-conductor technology.

The next diagram shows the mantle from a mineralogical perspective.

Energy considerations have hardly been mentioned, but this is already too long so apart from this quote about energy matters in outer space, discussion here on the subject will have to wait.

… Here we demonstrate that escape of positrons released in the decay of the short-lived radionuclide 26-Al leads to a large-scale charging of dense pebble structures, resulting in neutralisation by lightning discharge and flash-heating of dust and pebbles …

-Harvesting the decay energy of 26-Al to drive lightning discharge and chondrule formation. A. Johansen and S. Okuzumi Lund Observatory, Lund University

After saying that here is a bit of speculation about possible mass/energy processes that could occur in the underworld. 🙂

The prospect of a large proportion of mantle being composed of magnesium and calcium silicates and oxides doesn’t immediately bring accretion to mind, well not in my opinion at least, but rather some bulk production process. We presume phase transitions take place from the outer to the inner layer as per the gravitational accretion model.

Accretion requires that we think of the mantle the process as changes from the top down but a bulk authigenic process is more suggestive of a radial or centre out/bottom up process. In this view the crust becomes the first and oldest growth/inflation phase. A centre-out formation has a progression from more to less homogeneous material and the exothermic boundary reactions become endothermic and vice versa.

The centre-out view creates the prospect of some bulk conversion process where the oxygen, silicon and magnesium originate from the iron that is presumed to be in the core. Iron (26) can yield silicon (14) and magnesium (12) or three oxygen’s (8) with room to spare. Transformations may be sufficient to account for the significant volumetric increase/density decrease required.

Note too that magnesium (12), aluminium (13) and silicon (14) follow one another in proton number. So one can imagine another possibility whereby silicon releases one or two protons (as hydrogens (1) or helium (2) ) and transmutes into magnesium (12) or aluminium (13). And considering that oxygen is 94% by volume it is hard to avoid speculation about a variation in this ratio in an inflation process. Of course the possibility remains that such a process developed after accretion reached a critical mass that initiates the process.

Finally the large variation in magnesium content between the crust and the mantle (2% vs 22.8% by mass) might provide an explanation as to why, if expansion has actually occurred, the mantle inflated while the crust cracked and split. Perhaps whatever it was that caused the inflation had something to do with the production of magnesium. And perhaps the cracking of the crust is due to the absence of this process (suggesting perhaps that formation of the mantle and formation of the crust may have occurred in different epochs). This hypothetical process may initiate at different regions of the mantle at different times. We also have to consider that conditions may change over time, and we can’t altogether discount the existence of voids at some scale.